The Middle Passage was one side of the triangular trade routes. It indicated the forced journey of enslaved African men and women across the Atlantic Ocean.

THE SLAVE SHIP – FLOATING PRISON AND FORTRESS

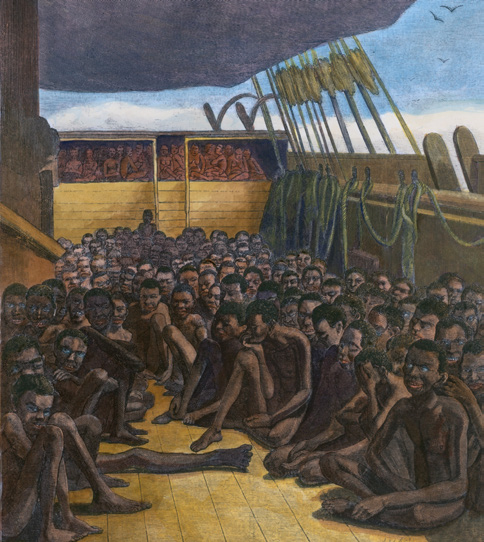

Each ship carried several hundreds of male and female slaves. Men were herded together and kept below deck in extremely narrow spaces, to make the most of the ship’s capacity and increase profits from the sale of slaves. Women and children were generally kept on the deck of the ship, in spaces which were separate from men.

“Naked, chained, very narrow steel collars sealed under their Adam’s apples, withered shoulders, their crazy eyes rolling, both revolted and surprised to find themselves on this gigantic construction from another world, their fists clenching while their hobbled feet struggled to find a precarious balance. The sentries had lined them up two by two for the outrageous inspection of their anatomy […].”

Wilfried N’Sondé, Un océan, deux mers, trois continents, Arles, Actes Sud, 2018 [Translation from French by Biblioteca Amilcar Cabral]

Unknown Author

Musée de la Compagnie des Indes, Port Louis, Francia

Wikimedia Commons

The ship carried 609 slaves: 351 men, 127 women,

90 boys and 41 girls

Plymouth Chapter of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade US-LibraryOfCongress-BookLogo.svg

Wikimedia Commons

Everett Collection

Shutterstock

Thomas Branagan, The penitential tyrant, New York, 1807

Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Olaudah Equiano‘s account of his arrival on the slave ship

“The first object which saluted my eyes when I arrived on the coast was the sea, and a slave ship, which was then riding at anchor, and waiting for its cargo. These filled me with astonishment, which was soon converted into terror when I was carried on board.

[···] When I looked round the ship [···] and saw a large furnace or copper boiling, and a multitude of black people of every description chained together, every one of their countenances expressing dejection and sorrow, I no longer doubted of my fate; and, quite overpowered with horror and anguish, I fell motionless on the deck and fainted.”

Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa the African, Gloucester, Dodo Press, 2009

Diseases associated with inadequate food and harsh conditions of detention were commonplace and were the leading cause of death among slaves and sailors. Dysentery, malaria, yellow fever, smallpox, measles, influenza, dehydration decimated the ‘human cargo’ of slaves. The corpses of the slaves were thrown into the sea.

An estimated 1.8 million human beings died during the Atlantic Ocean crossing.

Painting by Johann Moritz Rugendas, 1830

Museo Itaú Cultural, San Paolo del Brasile

Wikimedia Commons

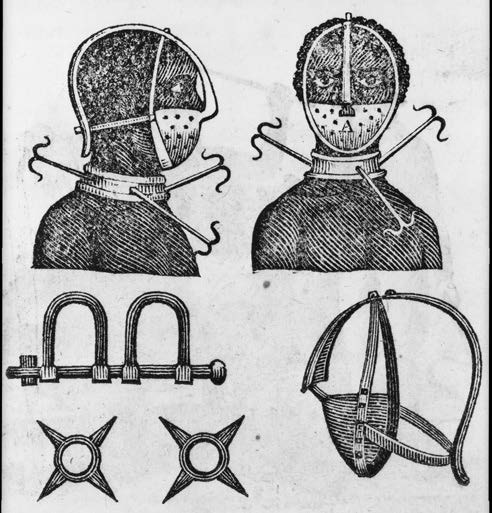

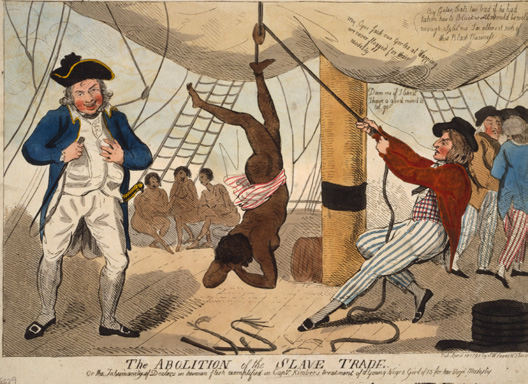

VIOLENCE AND POWER

The ship’s captain exercised absolute power over the crew and the cargo of enslaved men and women. Violence and terror were the weapons at the captain’s disposal to maintain order and discipline, to prevent the mutiny of the exploited and poorly paid sailors and the rebellion of the captives. The control of the African slaves was ensured by means of detention and repression that made the slave ship a ‘floating prison’.

Under the pretext of getting air and exercise, male and female slaves were forced to dance on the ship’s deck. Many refused to do it or did it unwillingly. These attitudes and behaviours, as well as food refusal, were regularly punished by the captain with a whip.

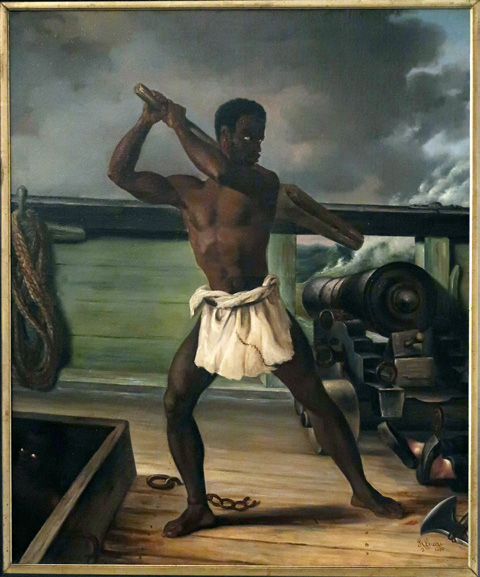

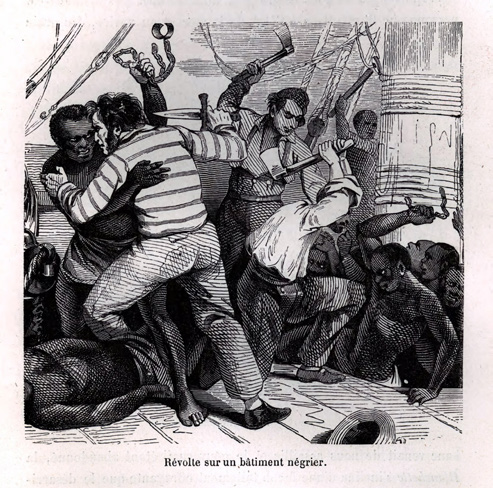

RESISTANCE AND REBELLION

Although the slave ship functioned as a ‘concentrationary microcosm’, African captives pursued various forms of passive and active resistance.

Suicide attempts were frequent: men and women refused to be treated as a ‘commodity’ and threw themselves into the sea. The attempts were so numerous that ships were equipped with net systems along the sides to prevent slaves from climbing over them and throwing themselves overboard.

There were hundreds, maybe thousands, of insurrection attempts to take over the ship, which often failed due to the military superiority of the crew.

Painting by Édouard-Antoine Renard, 1839

Musée du Nouveau Monde, La Rochelle

Wikimedia Commons

Albert Laporte, Récits de vieux marins, Paris, 1883?

Library Company of Philadelphia | Books & Other Texts | Rare | Am 1883 Lap 7206.Q (Lewis) p 267

Slavery Images

The illustration on the left shows John Kimber, captain of the ship Recovery en route between present-day Nigeria and the West Indies in 1791, with a whip in his hand and an African girl suspended upside down in the air. The story of the unnamed girl, sick and whipped to death for refusing to dance and eat, was denounced to the British Parliament by the abolitionist MP William Wilberforce and became a case of great resonance. The illustration by the famous Scottish caricaturist Isaac Cruikshank had a huge circulation and contributed decisively to spreading support for the abolitionist cause.

Charles Van Tenac, ed., Histoire Générale de la Marine Comprenant les Voyages Autour du Monde, Paris, 1847-48, vol. 4

Slavery Images

Zong

The terror imposed by the captain sometimes went as far as the mass murder of slaves. One case of massacre was that of the ship Zong, captained by Luke Collingwood, in 1781.

Under the pretext of a shortage of drinking water, the ship’s captain decided to get rid of some of the slaves on board, tying up and throwing 122 individuals into the sea; another 10 committed suicide by jumping overboard in terror.

The Zong case was not the only one. Throwing some of the slaves into the sea for reasons of convenience was not uncommon, as shown by the woodcut on the left, which illustrates the drowning in the port of Rio de Janeiro of sick slaves that would have remained unsold and on whom owners would have had to pay import duties.

Nathaniel Jocelyn, 1840. New Haven Colony Historical Society

Slavery Images

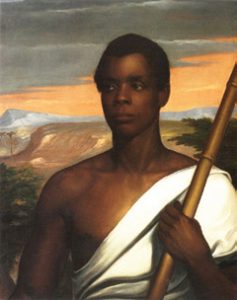

Amistad

One of the most famous and successful revolts was that of the Spanish ship Amistad. On the night of June 30, 1839, 53 slaves from West Africa, led by Sengbe Pieh (who later became known in the United States as Joseph Cinqué), killed the captain and the ship’s cook and forced the crew to divert their course to Connecticut, a non-slaveholding state, where they were captured and put on trial. Thanks to a vigorous abolitionist campaign in their support, they were acquitted, as they were considered victims of kidnapping, and sent back to Sierra Leone.

<<< Capture and voyage Arriving in the Americas >>>