Tapestry with polychrome cotton applications, cm 175×105, made in Abomey, Benin, 2007-2009

L’Océan Noir by William Adjété Wilson

Courtesy of the author

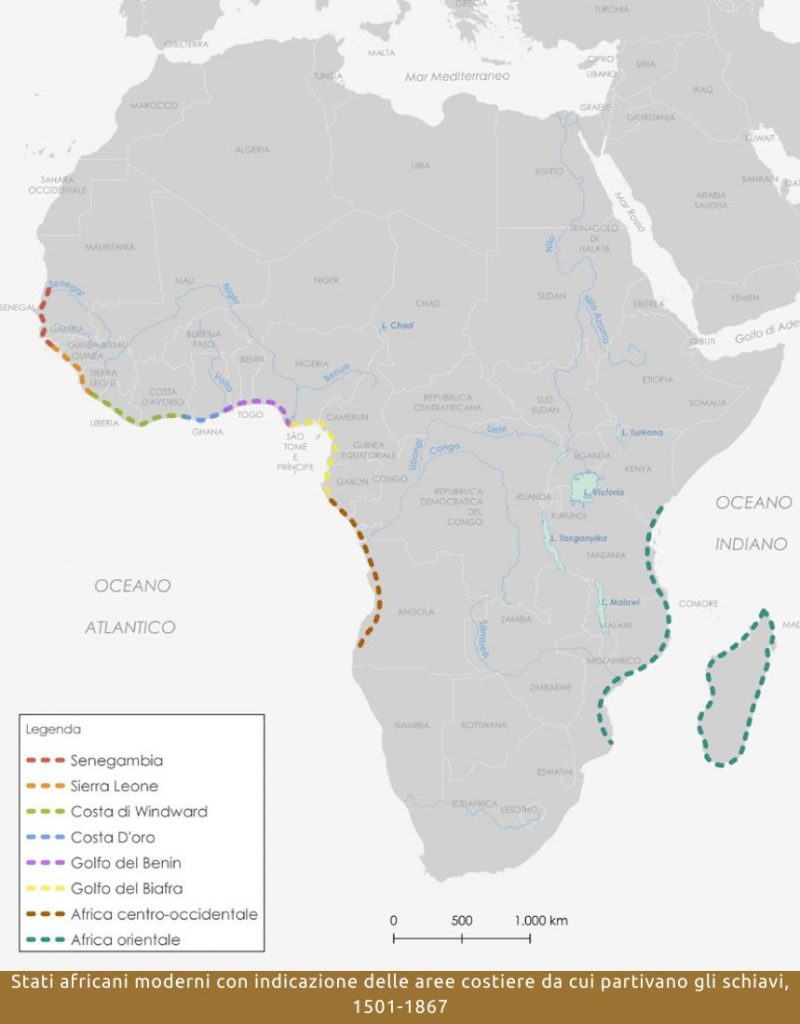

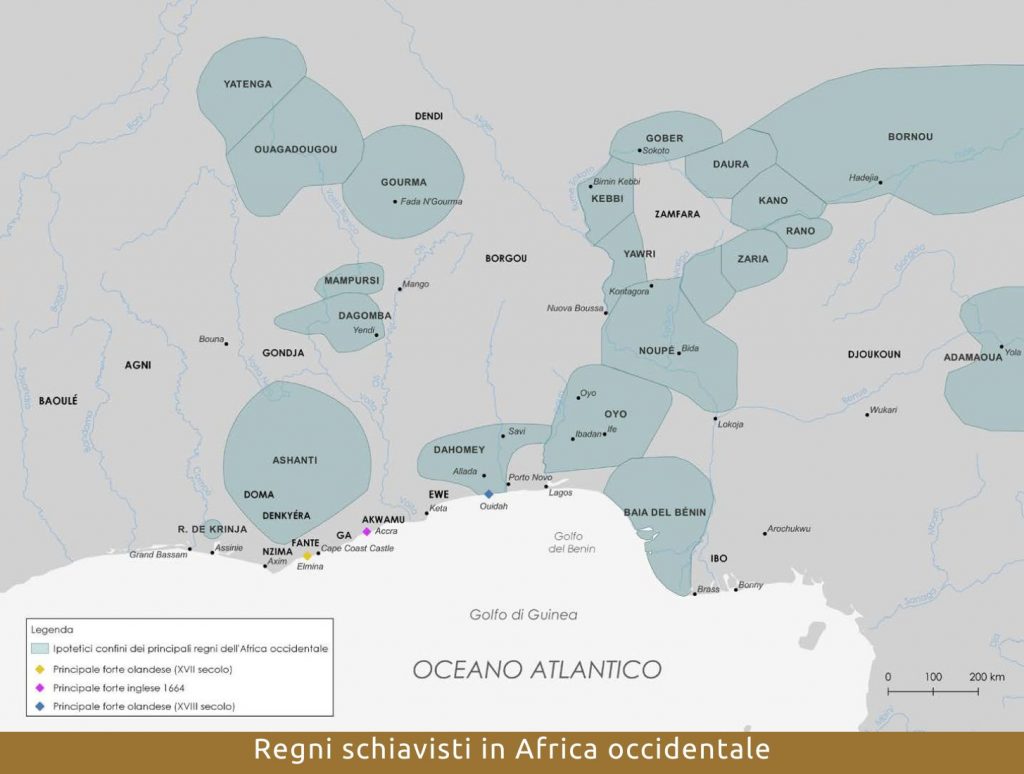

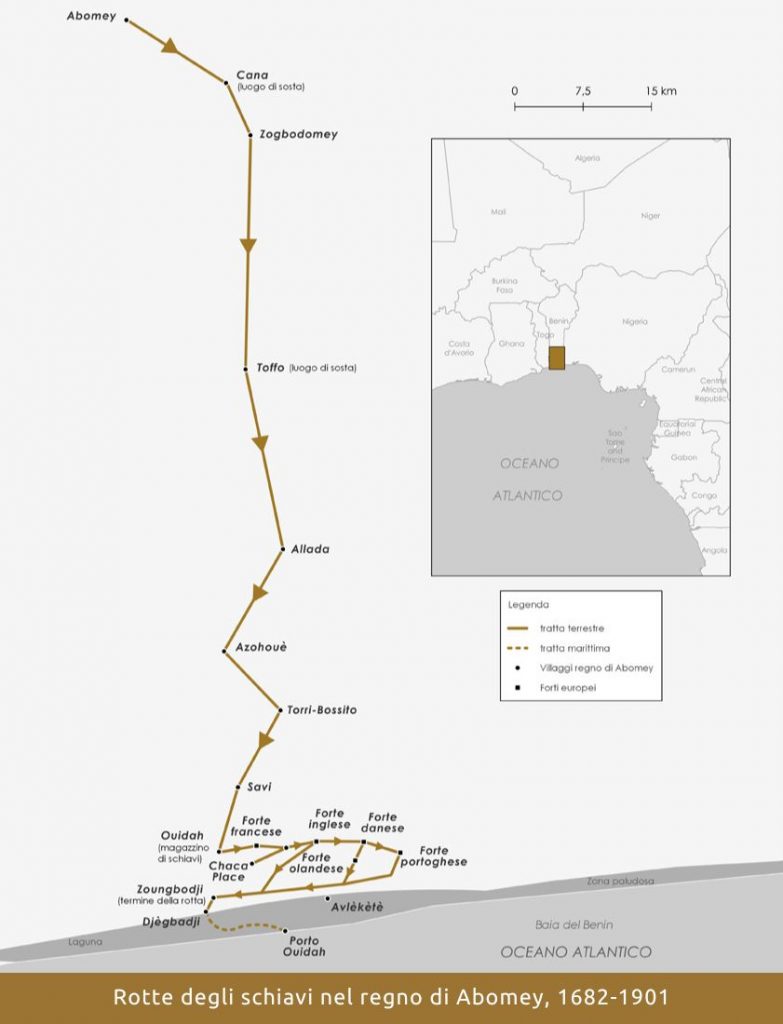

The slave trade was based on cooperation between European traders and African political authorities. Europeans settled in forts along the coast where they waited for the arrival of captives. African agents and traders in the service of inland kingdoms of the interior took care of the capture and transport to the coast. Thanks to their participation in the slave trade, these kingdoms built political power and accumulated enormous wealth.

Prisoners were transported to the coast by land or along

rivers, embarking on journeys that could last up to several months. It has been estimated that during the journey to the coast about 10 percent of captives lost their lives from disease and abuse.

African societies defined precisely who could and could not be enslaved. Slaves were generally the victims of raids and were taken as prisoners in wars between African peoples. In some cases it could happen that kings also sold their own subjects. However, this practice caused a series of popular rebellions, as in the case of the ‘Marabout War’ in Senegambia. Marabouts were itinerant Muslim teachers and preachers. One of them, Nasir al-Din, led a rebellion in the 1670s, which overthrew the king of Futa Toro – a region near the Senegal River -, accused by marabouts of selling his subjects to European slave traders.

Foto di Koreller

Musée d’histoire de Nantes

Wikimedia Commons

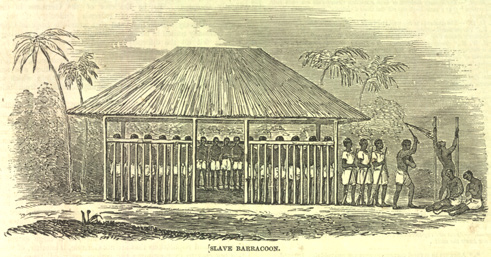

Fonte: William O. Blake, The History of Slavery and the Slave Trade, Columbus, Ohio, 1857, p. 97

Slavery Images

The National Archives, London, FO 84/1070

Slavery Images

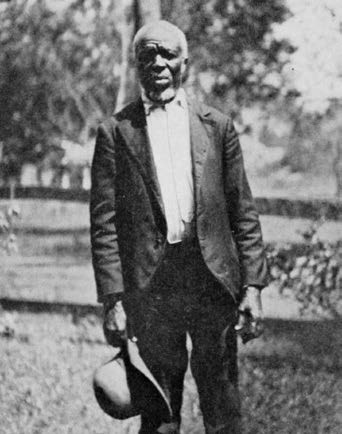

“Den de white man lookee and lookee. He lookee hard at de skin and de feet and de legs and in de mouth. Den he choose.“

Cudjoe Lewis

E.J. Glave, The Slave-Trade in the Congo Basin, in «The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine», 1889-1890, vol. 39, pp. 824-838

Slavery Images

Anthony Tibbles (a cura di), Transatlantic Slavery: Against Human Dignity, London, HMSO, 1994, p.102, fig. 23

Slavery Images

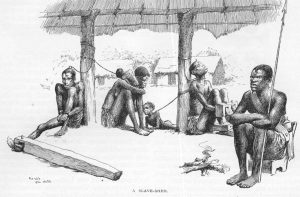

Il fiume Congo era un’importante via di commercio lungo la quale gli schiavi venivano trasportati verso la costa per essere venduti agli europei.

E.J. Glave, The Slave-Trade in the Congo Basin. By one of Stanley’s pioneer officers. Illustrated after sketches from life by the author, in “The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine”, 1889-1890, vol. 39, pp. 824-838

Slavery Images

The African captives were taken to coastal slave ‘warehouses’, that is structures such as forts, commercial buildings, barracoons, built and controlled by European merchants.

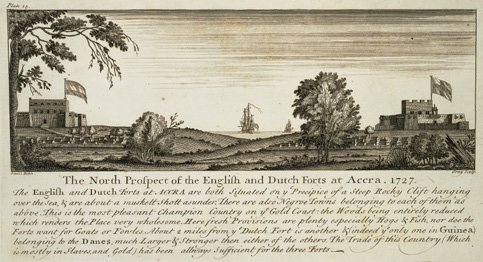

The Portuguese, the English, the Dutch, the French and the Danes built dozens of forts along the coasts of Atlantic Africa, with the aim of establishing monopoly areas on the slave trade and asserting their supremacy over the competing powers.

Captives arriving on the coast were examined and, if considered suitable, they were purchased by European trading companies and captains. They were therefore branded with the initials of the merchant owner of the ship both to sanction the purchase and to prevent them from being exchanged with other individuals deemed to be of lower ‘quality’.

Purchased slaves were then kept in forts or barracoons until slave ships off the coast were ready to leave and transport them across the Atlantic.

«The Illustrated London News», April 14, 1849, vol. 14, p. 237

Slavery Images

William Smith, Thirty Different Drafts of Guinea, London, 1727, tav. 25

Slavery Images

THE STORY OF CUDJOE LEWIS

«[···] dey march us to esoku (the sea).

[···] When we git in de place dey put us in a barracoon [···]

[···] Cudjo see de white men, and dass somethin’ he ain’ never seen befo’. In de Takkoi we hear de talk about de white man, but he doan come dere.

[···] When we dere three weeks a white man come in de barracoon wid two men of de Dahomey. One man, he a chief of Dahomey and de udder one his word-changer. [···] Den de white man lookee and lookee. He lookee hard at de skin and de feet and de legs and in de mouth. Den he choose. Every time he choose a man he choose a woman. Every time he take a woman he take a man, too.»

From Zora Neale Hurston, Barracoon: the story of the last black cargo, by Zora Neale Hurston, HarperCollins, 2018.

Photo by Emma L. Roche, 1914

Historic Sketches of the South, New York, Knickerbocker Press, 1914

Wikimedia Commons

Cudjoe Lewis, alias Oluale Kossola, at the time his testimony was collected was considered the last enslaved person still alive in the United States. Captured in the Kingdom of Dahomey region in modern Benin, he arrived in America aboard the last slave ship, the Clotilda, in 1859. The ship was wrecked and burned to hide evidence of the illegal trade.