THE HISTORY OF GORÉE

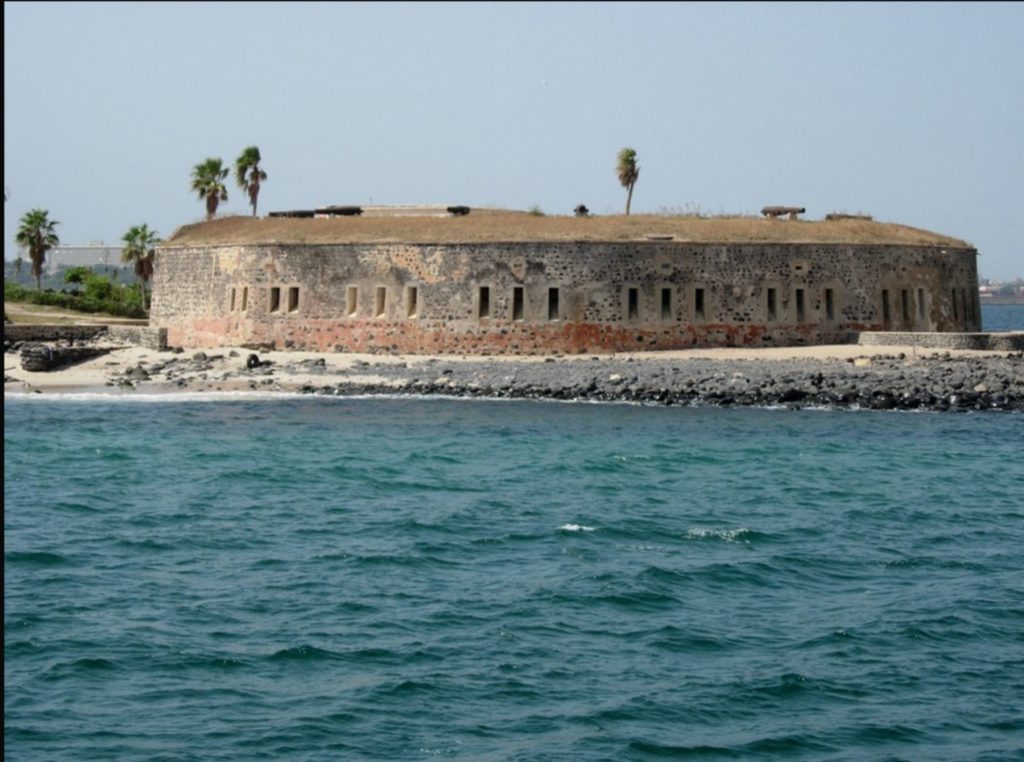

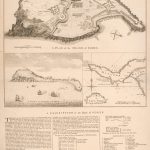

The island of Gorée – located 3.5 km off the coast of Senegal – played a very important role in African history: its location in the middle of the Atlantic routes and close to the continent, facilitated trade with the coastal kingdoms.

Shutterstock

In the 15th century, Europeans began to explore the West African coast and set up trading posts there, thus triggering the phenomenon that the Portuguese historian Magalhães Godinho called the victory of the caravel over the caravan: a gradual shift of trade routes from the Sahara desert, crossed by caravans connecting West Africa to the Mediterranean, to coastal regions. As Senegalese historian Boubacar Barry notes, this caused a political fragmentation which led to the rise of many African coastal states, such as Kajjor, Waalo and Djoloof.

The Portuguese arrived in Gorée in 1444 and remained there until 1621, when they were defeated by the Dutch, who occupied the island (except for a brief period of British domination) until 1677, the year in which France assumed control.

The island served as a resting and transit place for enslaved Africans before being loaded onto ships bound for the Americas: to house them, several buildings were constructed, including what has now become the Maison des Esclaves museum.

The illustrator F. B. Spilsbury in his Account of a voyage to the Western Coast of Africa (London, Richard Phillips, 1807, p. 4) writes:

«The riches of the inhabitants consist of slaves, each house having a slave yard, with huts for them; among the female slaves are many elegant figures […]. The slaves of both sexes are naked, except the piece of cloth which passes round the loins. The females do all the drudgery, such as beating corm, etc., with their children at their backs […]».

Signare Anna Colas’ house painted by d’Hastrel de Rivedoux in C.E. 1839

Wikimedia Commons

Engraving by Levasseur Atlas National de la France Illustrée

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Signare

An important cultural legacy of the European occupation remains on the island: on the one hand, the stone buildings, still visible today, used both as residences for the settlers and as warehouses for the slaves; on the other hand, an intangible heritage represented by the spread of a partly African and partly European culture, exemplified by the figure of the Signare, a term obtained by mispronouncing the Portuguese word senhora (lady). Daughters of enslaved African women and European men, the Signare inherited houses and wealth, mainly coming from the slave trade, from their fathers.

Polychrome engraving by Adolphe d’Hastrel

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

Born of a French father and a Signare mother, Abbot David Boilat is one of the first Senegalese writers to describe the history and society of his time in his book Esquisses Sénégalaises (1853). He depicts the arrival on the island of a shipload of slaves:

«On 2 July 1846, two hundred and fifty blacks of both sexes, caught in the Gulf of Guinea, were unloaded from a three-masted slave ship, named the Elizia. The whole town was present at this touching spectacle. What a horror, to see two hundred and fifty walking skeletons […] barely able to drag themselves! The signares shed bitter tears […]».

[Translation from French by Biblioteca Amilcar Cabral]

GORÉE, PLACE OF MEMORY

Senegal was affected by the Atlantic slave trade between 1451 and 1867, but the actual role of Gorée in the trade is debated by historians, who disagree on the number of slaves who passed through the island. However, Gorée is today recognised as one of the world’s best-known places of memory of the Atlantic slave trade, thanks to its inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1978 and the presence of the Maison des Esclaves, with its Door of No Return. This is the door through which slaves had to pass to board ships and in the popular imagination it has come to represent the moment when slaves last touched African soil.

Wikimedia Commons

Photo by Jeff Attaway

Flickr

Wikimedia Commons

Photo by Pete Souza

The White House – President Barack Obama

Wikimedia Commons

The slave trade gave rise to one of the largest diasporic communities in the world, with groups scattered all over

the planet: for many of them West and Central Africa is still their native land today.

Many Afro-Americans and Afro-Caribbeans have long started showing interest in the search for their origins, undertaking the same journey across the Atlantic made by their ancestors, but in reverse: memory tourists retrace their routes, in search of a lost and often mythologized origin. In fact, the physical places of this journey back home are no longer the same as those of the past and therefore take on a symbolic value.

With its Maison des Esclaves and the Door of No Return, Gorée has become the worldwide symbol of the slave trade since the late seventies, also thanks to the narrative related

by the museum’s first curator, Joseph N’Diaye, and to its recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

In 1933 Robert Gaffiot, colonel of the colonial infantry, published his book entitled Gorée Capitale déchue, in which he described the warehouse better known as the Maison des Esclaves: here, on the ground floor, prisoners were crammed and, very often, chained in long, narrow cells. Captured people were locked up in these cramped places for the time necessary to fill the slave ships ready to leave for the Americas.

Gorée’s international role as a universal symbol of the suffering, injustice and economic exploitation brought about by the Atlantic slave trade is recognised and boosted thanks to the visits made over the years by several polital leaders , such as Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Nelson Mandela, Jacques Chirac and Barack Obama, religious figures such as Pope John Paul II, musicians, including James Brown and the Jackson 5, sports stars, such as Muhammad Ali and Pelé, and celebrities from the world of cinema, such as Spike Lee and Danny Glover.

It is not a form of tourism, but rather a pilgrimage to a sacred place.

«Terror seized us as soon as we entered. […] In these gloomy impasses, the complaints of the captives were only drowned out by the incessant noise of the ocean backwash on the blackish pebbles, and God only knows how many corpses passed through the doors […] overlooking the sea to be fed to sharks!».

Robert Gaffiot

[Translation from French by Biblioteca Amilcar Cabral]