THE ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE: broken lives between Africa and the Americas

It is often said that in Africa slaves had no shadow under the scorching midday sun.

This exhibition aims to restore the shadow to men, women, boys and girls who were captured and violently transported beyond the Atlantic Ocean and who – as one of the last enslaved persons of the Atlantic slave trade, Cudjoe Lewis, recalled – lookee and lookee and lookee and […] doan see nothin’ but water. At last, at the end of a long journey aboard floating prisons, the slaves were thrown and dispersed into a new and totally unknown universe.

It aims to outline the context of the forgotten stories of men and women who in their millions (between 11 and 13 according to historians’ estimates) were victims of a complex and violent system of trade, complicities and alliances between African potentates and aristocracies on the one hand, and European and American states, merchants, bankers, planters, captains on the other.

It also tries to restore the voice, body and identity to the men and women who responded to the violence of the Middle Passage by becoming the protagonists of the history of the slave trade: resisting, rebelling, fleeing, negotiating, building family and community ties, inventing new languages, cultures and forms of art, fighting for the abolition of slavery.

The exhibition takes the visitor on a journey through time and space.

Over time since it retraces four centuries of history which from the end of the fifteenth century to the end of the nineteenth century marked the birth, development and final abolition of the transatlantic slave trade as a legal business commerce which eventually became the cornerstone of the emerging capitalist system.

In space since slave trade connected the history of the two sides of the Atlantic Ocean in a global order, turning them into a space for interchange of goods, – including human beings considered ‘movable goods’ subject to private property -, ideas and cultural constructs. The concept of race emerges in connection with the slave trade and will be used to justify the enslavement of human beings considered inferior and to erect a hierarchical order based on the categories of white and black.

Although slavery has been legally abolished and is now sanctioned by international law, its consequences continue to operate and reproduce in relations of domination which are far too often considered as natural and taken for granted, reinforcing more or less explicit forms of structural and everyday racism. The explosion of the Black Lives Matter movement powerfully reminded us of this. Understanding the origins, history and contemporary legacies of the Transatlantic slave trade is the ambition of this exhibition.

INTERVIEW WITH CRISTINA ERCOLESSI, CURATOR OF THE EXHIBITION (in Italian language)

LISTEN

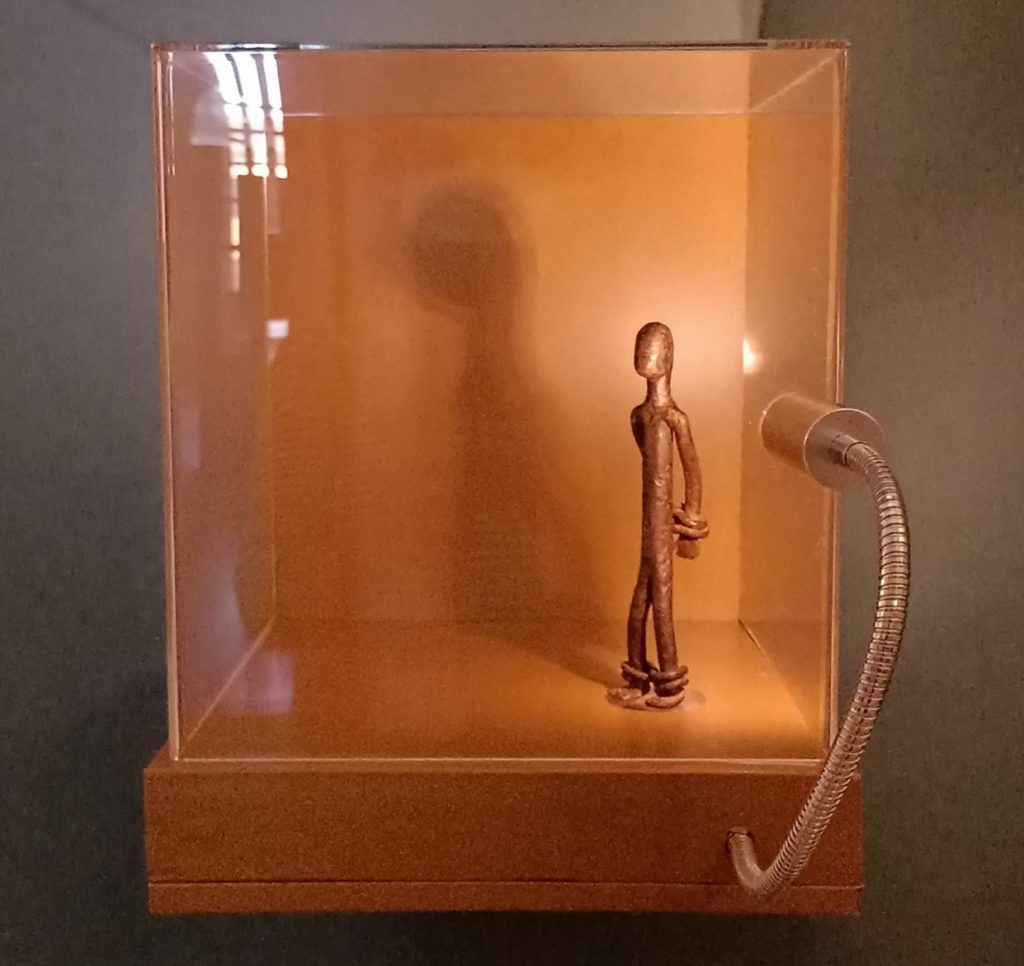

patinated iron H 15 cm., probably early 19th century. Mali

Augusto Panini Collection

The small statue on the side is in forged iron known as ‘fer noir’ and belongs to the private collection of Augusto Panini. It represents a chained slave from the village of Bougouni in the Sikasso region of southern Mali. It is an object probably linked to the cult of ancestors: a Mandingo man destined for the slave trade between the coast of Guinea and the Americas, a sad legacy of the 17th-18th centuries when more than five million Africans were enslaved. The memory of this tragic period is very vivid in the people who suffered this abomination in Benin, Nigeria, Ghana, Mali and Senegal.

*********************************************************************

Quotations of original texts dating back to the 18th-20th centuries may contain terms and words in use at that time and now considered unacceptable and offensive.

In recent years, the use of the terms ‘slave’ and ‘enslaved person’ has given rise to a discussion among historians (in particular the English-speaking ones). The word ‘slave’ is believed to obscure the humanity of the person subjected to slavery, while the adjective “enslaved” wants to emphasize that the state of slavery is imposed and not intrinsic to the identity of the person. Though we are aware of the linguistic difference, the two terms are used interchangeably in the following texts.

Historical images are mostly paintings, prints, drawings or illustrations created during the slave period by authors who did not often have first-hand knowledge of what they represented. Historical images therefore reflect prejudices of European or American authors, their exoticizing imagination and their romantic idealizations. They are rarely representations of reality. It is for this reason that, if they are not overtly racist, they cast paternalistic feelings onto African slaves.