Although Africans were employed in a variety of labour sectors (from road construction to domestic work to mining) the vast majority were used in plantation agriculture.

American plantations were generally large and specialised in the cultivation of a single commodity (sugar cane, cotton, coffee, cocoa, indigo, rice, tobacco, corn) and required large amounts of labour.

Societies based on the plantation system were polarised and hierarchised: they were politically dependent on colonial authorities and dominated by an elite of planters of European origin and, to a lesser extent, of mixed origins (Creole), who controlled a large slave population uprooted from their places of origin, and exercised a high degree of violence.

Colonial codes and legislation were introduced to legitimise and institutionalise the racialisation of social relations and support the development of plantations.

SUGAR CANE

Almost half of the slaves imported over the centuries were destined for sugar cane plantations in Brazil, the Caribbean and the United States.

In particular, in the Antilles, sugarcane plantation included all three stages of production: cultivation of the land, produce processing, transport and sale to European traders.

The plantation operated on the basis of a complex division of labour. In the fields, slaves worked for many hours a day to plant, cultivate, cut and harvest cane. They then had to transport the cane to a mill, driven by water or animal power, where the juice was extracted and turned into molasses, sugar and rum.

Other slaves performed specialised jobs, such as carpenters, blacksmiths and bricklayers.

A high number of domestic workers were also employed on plantations, while others had to grow the food needed to feed the plantation population. Child labour was also widely used both in the fields and in domestic activities.

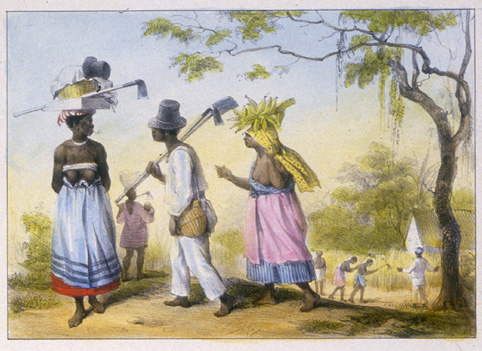

Pierre Jacques Benoit, Voyage à Surinam: description des possessions néerlandaises dans la Guyane, Bruxelles, Société des Beaux-Arts de Wasme et Laurent, 1839, Fig. 39

Slavery Images

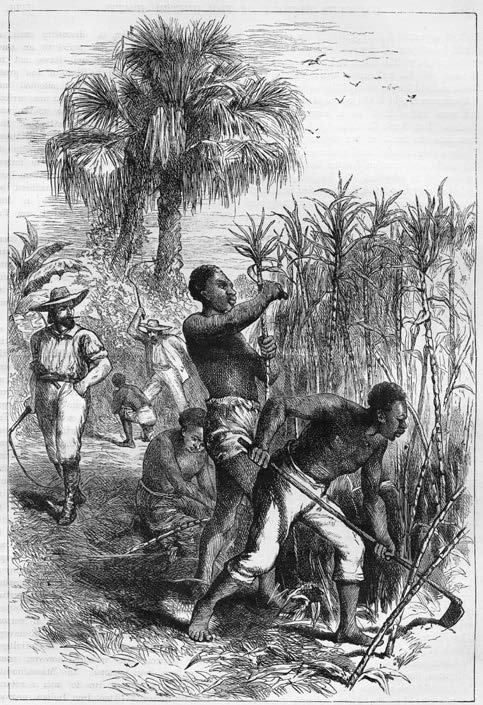

Edmund Ollier, Cassell’s History of the United States, London, 1874-77, vol. 2, p. 493

Slavery Images

Cotton belt/Black belt

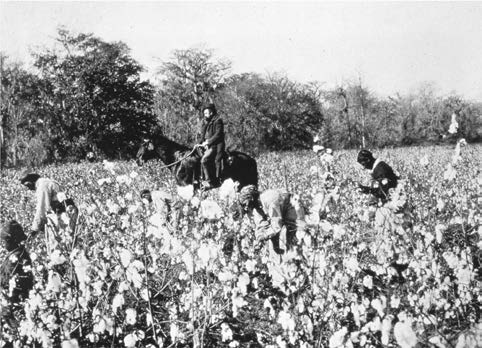

«Frank Leslie’s Boy’s and Girl’s Weekly», Oct. 2, 1869, vol. 6, n. 154, p. 380

Slavery Images

In November 1785, the first seven bales of North American cotton landed in the port of Liverpool. Within a few decades, cotton produced in the southern United States will experience astronomical growth thanks to two main factors:

– the discovery of a variety of cotton which was resistant and particularly suitable for being processed by the mechanical cotton gin, used to separate the cotton fibres from the rest of the plant

– the territorial expansion of the South through the acquisition of new land by white farmers, made possible by the forced expulsion of native populations with the Indian Removal Act (1830).

At the end of the 1830s, cotton had become the main crop not only in the South but in the entire United States, and more than half of U.S. exports now consisted of cotton.

Slave labour was essential to the growth of Southern cotton production. Cotton and slavery became inseparable and grew hand in hand.

The economic importance of slavery is highlighted by the price of slaves themselves. In the 1840s and 1850s, the price of slaves doubled compared to the previous decade, following the trend in cotton prices.

Photo by unknown author

Wikimedia Commons

“Niggers and cotton—cotton and niggers; these are the law and the prophets to the men of the South.”

James Stirling, Letters from the Slaves States, London, Parker, 1857, pp. 179–180

«To sell cotton in order to buy negroes – to make more cotton to buy more negroes, ‘ad infinitum’, is the aim […] of all the operations of the thorough-going cotton planter; his whole soul is wrapped up in the pursuit.»

Joseph Holt Ingraham, The Southwest by a Yankee, New York, Harper, 1835, Vol. 2, p. 91.

Frederick M. Coffin (engraved by Nathaniel Orr), in Solomon Northup, Twelve years a slave, Auburn, Derby and Miller, 1853

Wikimedia Commons

A day’s work on a cotton plantation in Louisiana

«The hands are required to be in the cotton field as soon as it is light in the morning, and, with the exception of ten or fifteen minutes, which is given them at noon to swallow their allowance of cold bacon, they are not permitted to be a moment idle until it is too dark to see, and when the moon is full, they often times labor till the middle of the night. They do not dare to stop even at dinner time, nor return to the quarters, however late it be, until the order to halt is given by the driver.

The day’s work over in the field, the baskets are ‘toted’, or in other words, carried to the gin-house, where the cotton is weighed. No matter how fatigued and weary he may be- – no matter how much he longs for sleep and rest- – a slave never approaches the gin- house with his basket of cotton but with fear. If it falls short in weight- – if he has not performed the full task appointed him, he knows that he must suffer. And if he has exceeded it by ten or twenty pounds, in all probability his master will measure the next day’s task accordingly.»

Solomon Northrup, 12 anni schiavo, Garzanti, 2014 pp. 143-144