Resistance to slavery arose right from the moment of arrival in the Americas, with individual and collective attempts to escape to the coasts.

On the plantations, slavery conditions were opposed with individual acts of resistance such as committing suicide, renouncing food, disobeying masters and overseers, sabotaging goods or work tools, pretending to be sick, stealing food or other consumer goods.

Photo by Charles Hoffman

Wikimedia Commons

ESCAPES AND MAROONS

Individual or collective escape was for centuries the main strategy to get away from slavery. The term maroon refers to people who escaped from American plantations and established independent communities on the fringes of slave societies.

For more than four centuries, these communities dotted the entire American continent, from Brazil (where they were called quilombos) to the Spanish colonies in South America, from the Caribbean to the south of the present-day United States. Their existence could last a few weeks or many decades, forming independent communities with their own institutions and armies, usually led by a king.

Photo by Elza Fiúza, Agência Brasil, 21th november 2006

Wikimedia Commons

Palmares

Palmares was a famous Maroon community in northeast Brazil. It survived for a whole century until it was reconquered by the Portuguese in 1694/95. It consisted of a federation of villages, some of which with thousands of residents, inhabited mainly by Africans from Angola, who were joined by natives, poor whites and Portuguese deserters. Palmares managed to resist the Portuguese and Dutch attacks for a long time thanks to its complex social, political and military organisation, first under the leadership of Ganga Zumba, and then of the legendary Zumbi, who was eventually captured and beheaded. His head was displayed in Rio de Janeiro.

On 20 November 2010, Zumbi was declared a national hero by the Brazilian government which on that date proclaimed a Black Consciousness Day.

Frans Post, Parte sul da Capitania de Pernambuco, com representação do Quilombo dos Palmares, 1647

Wikimedia Commons

Shutterstock

THE BLUE MOUNTAINS IN JAMAICA

In Jamaica, Maroon riots and communities were a constant feature of life on the island. In the 1730s, Maroons of different origins settled in the east of the island, in the Blue Mountains.

The failure of the British military actions forced the governor to enter into an agreement with the Maroons which provided for the recognition of the community in exchange for promises to hand over new fugitives.

In 1795/96, a new war ended with the victory of the British and the loss of autonomy of the Maroon community.

For women, resistance could mean the refusal, through abortion, to procreate new slaves. The African American writer Toni Morrison, the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1993, in her novel Beloved represented the radical nature of this opposition by narratively reinterpreting the true story of the runaway slave Margaret Garner, who, before being recaptured, killed her daughter to prevent her from falling into slavery.

THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

The runaway slave became a central figure in the 19th century United States, before and during the Civil War (1861-65).

The escape usually involved a long and hard journey to the Northern states which had abolished slavery, or to Canada, with the constant danger of being recaptured, also by using specially trained dogs. Despite this, it is estimated that between 1800 and 1865, 70,000 individuals managed to escape from slavery, thanks to the Underground Railroad, a network of people, ‘conductors’ and safe houses that helped fugitive slaves escape to the North.

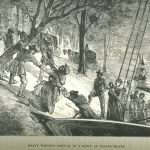

William Still, The Underground Railroad, Philadelphia, 1872, facing p. 561

Slavery Images

UPRISINGS AND REVOLTS

Armed rebellions against slavery swept across the Americas from South to North, affecting all colonial regimes. Armed revolts were the riskiest form of resistance for slaves. Indeed, colonial governors and planters did not hesitate to apply the harshest military repression, even if in some cases they were forced to come to terms, at least temporarily, with the rebels.

John Carter Brown Library

Revolution in Haiti

Uprisings gained momentum after the first successful revolt against the French colonial slave regime in Santo Domingo

(now the state of Haiti) in 1791. Led by the charismatic leader and former slave Toussaint Louverture, the rebellion ended in 1804 with the achievement of independence, the abolition of slavery and the creation of the first modern black state.

Its effects were felt throughout the American continent. The political and military skills of the rebels challenged the colonial assumption that slaves of African descent would not be able to assert and defend their freedom and govern themselves.

The spectre of ‘another Haiti’ began to haunt the American plantations.

Slavery Images

A song of enslaved Yamba, Cameroon

When we sit silent,

Are we men?

When we sit motionless

Are we women?

When we succumbed so easily

Are we children?

The more you push a calabash into the water the more it floats

Take courage, take action men

Our friends who escaped into the forest are many

Though their injuries are countless, they survived

These slavers took us like foxes pick up strayed chickens

Let us make them bow to us or we die

Let them know that we are men

Let them know we are heroes born to end this evil

From E.S.D. Fomin, “Slave Voices from the Cameroon Grassfields: Prayers, Dirges, and a Nuptial Chant”, in Bellagamba, Green, Klein (eds.), African Voices on Slavery and the Slave Trade – Vol. 1: The Sources, Cambridge University Press, 2013