John A. Waller, A Voyage in the West Indies, London, 1820

Slavery Images

COMMUNITY AND IDENTITY

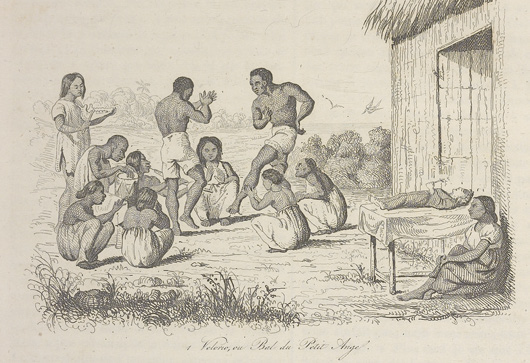

The traumatic experiences of slave trade gave rise in the Americas to a ‘culture of slavery‘ which blended elements of African cultures of origin and of places of arrival, such as Christianity. Especially in the plantation world, these ‘hybrid’ cultures helped forge community feelings which nurtured solidarity, circulation of news and expectations of liberation.

The family played a crucial role in the daily lives of enslaved people. Weddings and funerals were celebrated with rituals which often incorporated African cultural elements and served to strengthen symbolic bonds in a context in which relationships between husband and wife and between parents and children could be violently destroyed at any time.

Women were the most vulnerable, exposed to sexual violence, unwanted pregnancies, and the loss of children who could be sold at an early age.

Alcide Dessalines d’Orbigny, Voyage pittoresque dans les deux Amériques, Paris, 1836, facing p. 51

Slavery Images

FUNERAL OF A CHILD SLAVE

«[…] its father buried [with the child] a small bow and several arrows; a little bag of parched meal; a miniature canoe, about a foot long, and a little paddle, (with which he said it would cross the ocean to his own country), a small stick, with an iron nail, sharpened and fastened into one end of it; and a piece of white muslin, with several curious and strange figures painted on it in blue and red, by which, he said, his relations and countrymen would know the infant to be his son, and would receive it accordingly, on its arrival amongst them…»

Testimony of Charles Ball, a slave in western Maryland, 1858.

Fonte: Digital History

WEDDING CEREMONY IN THE SOUTHERN UNITED STATES

This engraving shows a wedding ceremony called ‘jumping the broom’. Probably derived from a ritual of the Asante kingdom (present-day Ghana), it consisted of waving brooms over the heads of the bride and groom to drive away spirits. After exchanging vows, the bride and groom jumped a broom while holding hands

Emily Clemens Pearson [pseudo. Pocahontas], Cousin Francks Household, or, Scenes in the Old Dominion, Boston, 1853

Slavery Images

PRAYING AND HEALING

One of the most powerful factors in the cultural identity of slaves was religion, accompanied by a variety of spiritual beliefs and practices, such as the use of divination and traditional African medicine.

Most of the religions developed in slavery which are still vital today – such as Voodoo in Haiti or Candomblé in Brazil – present a complex mixture of elements, rituals, names, spirits and saints, which can be traced back both to different parts of Africa and to a reinterpretation of the Catholic-Christian religion.

The most recent research has highlighted the importance of figures, especially women, who worked in the spiritual sphere and took care of people on plantations on the basis of medical and ritual practices of African origin and involved the use of local herbs.

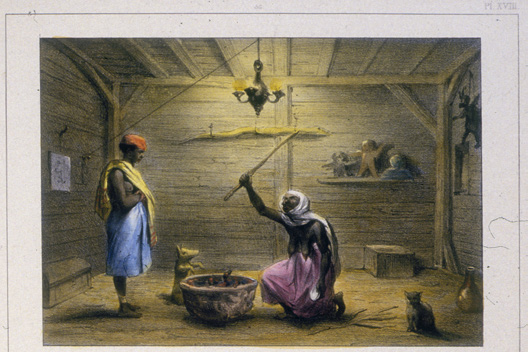

Pierre Jacques Benoit, Voyage à Surinam: description des possessions néerlandaises dans la Guyane, Bruxelles, Société des Beaux-Arts de Wasme et Laurent, 1839

Slavery Images

Painting by Ilunga, Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, unknown date

Congo Art Pop – Collezione di pittura popolare congolese di Bogumil Jewsiewicki, Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici, Università della Calabria

The lithograph shows a diviner engaged in ritual activities and in the preparation of a herbal infusion used to treat a child. The author, Pierre Jacques Benoit, reports that old women who practised traditional medicine were considered oracles and called Mama Snekie (Mother of Snakes) or Water Mama (Mother of Water), a figure widely spread on the African continent, associated with treatment and healing and often depicted as a mermaid.

The well-known black abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass recalled in his book My Bondage and My Freedom (1855):

«A keen observer might have detected in our repeated singing of

O Canaan, sweet Canaan,

I am bound for the land of Canaan,

something more than a hope of reaching heaven. We meant to reach the north—and the north was our Canaan.»

Likewise, the constant reference to the Jordan River, as in the lyrics of the song below, indicated the aspiration to escape and cross rivers such as the Mississippi or the Ohio which separated the slave-owning South from the North of the United States.

Roll Jordan, roll

Roll, Jordan, roll, roll, Jordan, roll,

I want to go to heaven when I die,

To hear Jordan roll.

Oh, brothers, you ought t’have been there.

Yes, my Lord!

A sitting in the kingdom,

To hear Jordan roll.

Roll, Jordan, roll, roll, Jordan, roll

Oh, mothers, you ought t’have been there.

Yes, my Lord!

A sitting in the kingdom,

To hear Jordan roll.

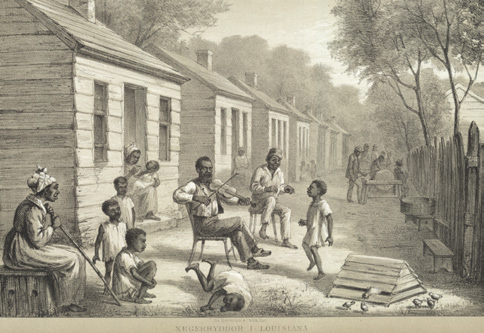

MUSIC AND DANCE

Over time, there was an important development of black congregations, led by preachers of African descent, and characterised by their own cultural styles. Biblical interpretations and metaphors became powerful tools to represent the condition of slavery and the aspiration for freedom, creating new musical genres such as spirituals and gospel.

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division (LC-B811-151)

Slavery Images

Pavel Petrovich Svinin, Opyt zhivopisnago puteshestviia po sievernoi Amerikie, St. Petersberg, 1815

Slavery Images

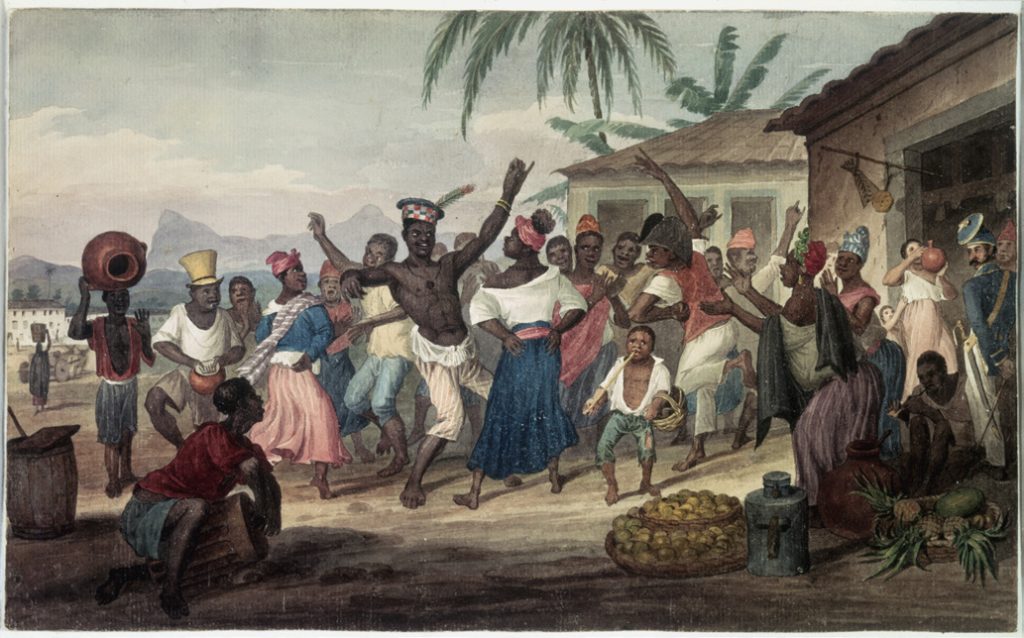

Augustus Earle (1793-1838)

National Library of Australia, Canberra

Slavery Images

Deprived of access to education and therefore to reading, slaves resorted to a wide repertoire of oral tradition, as was already the case in Africa.

Music played a fundamental role. Alongside religiously inspired songs, there were work songs, songs satirising masters and overseers, and the so-called sorrow songs, which lamented the sad and unbearable conditions of slavery.

Adolf Carlsson Warberg, Skizzer fran Nord-Amerikanska Kriget, 1861-1865. Bref och anteckningar under en fyraarig vistelse i Forenta staterna af en i detta krig deltagande svensk officer, Stockholm, 1867-71, facing p. 308

Slavery Images

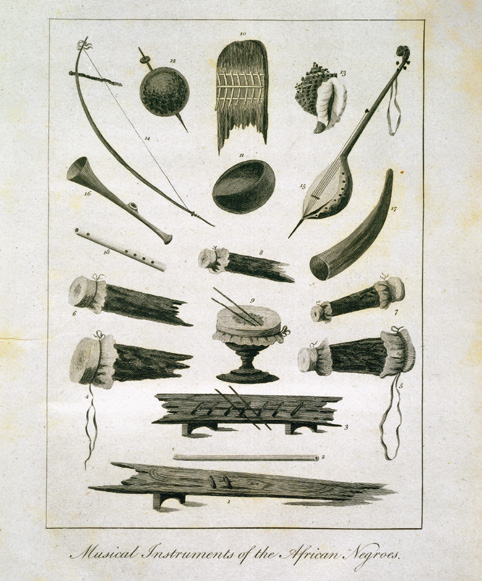

John Gabriel Stedman, Narrative, of a Five Years’ Expedition, against the revolted Negroes of Surinam . . . from the year 1772, to 1777, London, 1796

Slavery Images

Many of the musical instruments associated with African American music, including banjo and drums, derive from African instruments; likewise, some musical forms, such as the ‘call and response’ structure, also typical of the music which accompanies Brazilian capoeira, reflect African musical traditions.

On North American plantations, slaves listened to the preaching of various Protestant denominations and Bible reading, sometimes organised by the planters themselves. Autonomous religious practices were forbidden by the masters and therefore were kept hidden from their eyes, for example by keeping small altars hidden in the huts.